THE AUTO BUILDER

Featured

- All Post

- 20 High Priority - SR Super Rod

- Builds

- 25 High Priority - FB Ford Builder

- Cars

- 30 High Priority - AR American Rodder

- 01 Post Status

- 35 High Priority - RD Rodders Digest

- 40 High Priority - OTR On the Road

- 45 High Priority - SRB Street Rod Builder

- 50 High Priority - TB Truck Builder

- 55 High Priority - BSCENE Buckaroo Scene

- 60 High Priority - FPB Family Power Boat

- Trucks

- Swaps

- Performance Boats

- _000 Home Sliders

- Builders

- 00 Sidebars

- Manufacturers

- 05 High Priority - HCI Hot Compact Imports

- 05 Publications

- 10 High Priority - CR Chevy Rumble

- Back

- Chassis

- Engine

- Fuel System

- Electrical

- Exhaust

- Transmission / Drivetrain

- Suspension

- Steering

- Brakes

- Wheels and Tires

- Interior

- Exterior

- Accessories

- Power Adders

- Back

- Chassis

- Engine

- Fuel System

- Electrical

- Exhaust

- Transmission / Drivetrain

- Suspension

- Steering

- Brakes

- Wheels and Tires

- Interior

- Exterior

- Accessories

- Power Adders

- Back

- Chassis

- Engine

- Electrical

- Exhaust

- Fuel System

- Transmission / Drivetrain

- Suspension

- Steering

- Brakes

- Wheels and Tires

- Interior

- Exterior

- Accessories

- Power Adders

- Back

- Chassis

- Engine

- Electrical

- Exhaust

- Fuel System

- Transmission / Drivetrain

- Suspension

- Steering

- Brakes

- Wheels and Tires

- Interior

- Exterior

- Accessories

- Power Adders

- Back

- Chassis

- Engine

- Fuel System

- Electrical

- Exhaust

- Transmission / Drivetrain

- Suspension

- Steering

- Brakes

- Wheels and Tires

- Interior

- Exterior

- Accessories

- Power Adders

- Back

- Chassis

- Engine

- Fuel System

- Electrical

- Exhaust

- Transmission / Drivetrain

- Suspension

- Steering

- Brakes

- Wheels and Tires

- Interior

- Exterior

- Accessories

- Power Adders

- Back

- Chassis

- Engine

- Fuel System

- Electrical

- Exhaust

- Transmission / Drivetrain

- Suspension

- Steering

- Brakes

- Wheels and Tires

- Interior

- Exterior

- Accessories

- Power Adders

- Back

- Engine

- Fuel System

- Electrical

- Outdrives

- Steering

- Interior

- Accessories

- Power Adders

- Exterior and Hull

- Back

- Chassis

- Engine

- Electrical

- Exhaust

- Fuel System

- Transmission / Drivetrain

- Suspension

- Steering

- Brakes

- Wheels and Tires

- Interior

- Exterior

- Accessories

- Power Adders

- Back

- Chevrolet

- Cadillac

- Pontiac

- AMC

- Buick

- Jeep

- Lincoln

- Ford

- Honda

- GMC

- BMW

- Mitsubishi

- Dodge

- Nissan

- Chrysler

- Subaru

- Toyota

- Plymouth

- Mercury

- Volvo

- Volkswagen

- Oldsmobile

- Acura

- Back

- 05 Pub HCI Hot Compact Imports

- 15 Pub 4x4 4x4 Builder

- 20 Pub SR Super Rod

- 25 Pub FB Ford Builder

- 30 Pub AR American Rodder

- 35 Pub RD Rodders Digest

- 40 Pub OTR On the Road

- 55 Pub BSCENE Buckaroo Scene

- 10 Pub CR Chevy Rumble

- 50 Pub TB Truck Builder

- 60 Pub FPB Family Power Boat

- 45 Pub SRB Street Rod Builder

- Back

- Chip Foose

- Ring Brothers

- Jack Fuller

- Bob Cullipher

- Jerry Nichols

- Bobby Alloway

- Jesse James

- Carl Casper

- J.F. Launier

- Steve Sellers

- Boyd Coddington

- Rad Rides by Troy

- Cal Auto Creations

- George Barris

- West Coast Customs

- Back

- Street Rods

- Hot Rods

- Late Model

- Drag Race

- Handling

- Compact Cars

- Chassis

- Engine

- Fuel System

- Electrical

- Exhaust

- Transmission / Drivetrain

- Suspension

- Steering

- Brakes

- Wheels and Tires

- Interior

- Exterior

- Accessories

- Power Adders

- Chassis

- Engine

- Fuel System

- Electrical

- Exhaust

- Transmission / Drivetrain

- Suspension

- Steering

- Brakes

- Wheels and Tires

- Interior

- Exterior

- Accessories

- Power Adders

- Chassis

- Engine

- Electrical

- Exhaust

- Fuel System

- Transmission / Drivetrain

- Suspension

- Steering

- Brakes

- Wheels and Tires

- Interior

- Exterior

- Accessories

- Power Adders

- Chassis

- Engine

- Electrical

- Exhaust

- Fuel System

- Transmission / Drivetrain

- Suspension

- Steering

- Brakes

- Wheels and Tires

- Interior

- Exterior

- Accessories

- Power Adders

- Chassis

- Engine

- Electrical

- Exhaust

- Fuel System

- Transmission / Drivetrain

- Suspension

- Steering

- Brakes

- Wheels and Tires

- Interior

- Exterior

- Accessories

- Power Adders

- Chassis

- Engine

- Fuel System

- Electrical

- Exhaust

- Transmission / Drivetrain

- Suspension

- Steering

- Brakes

- Wheels and Tires

- Interior

- Exterior

- Accessories

- Power Adders

- Back

- 05 Post Imported

- 20 Post Missing Images (All)

- 25 Post Missing Images (Partial)

- 15 Post In Progress

- 30 Post Internal Review

- 40 Post On Hold

- 50 Post Approved

- 10 Post Images Imported

- 17 Post Missing TXT Files

- 18 Post Missing PDF Files

- 27 Post Missing Content

- Back

- Chassis

- Engine Swaps

- Interior Swaps

- Driveline

- Back

- Street Trucks

- OffRoad Trucks

- Chassis

- Engine

- Fuel System

- Electrical

- Exhaust

- Transmission / Drivetrain

- Suspension

- Steering

- Brakes

- Wheels and Tires

- Interior

- Exterior

- Accessories

- Power Adders

- Chassis

- Engine

- Fuel System

- Electrical

- Exhaust

- Transmission / Drivetrain

- Suspension

- Steering

- Brakes

- Wheels and Tires

- Interior

- Exterior

- Accessories

- Power Adders

- Back

- 01 Sidebar Left

- 01 Sidebar Right

Spotlighter

POPULAR READS

-

Product Spotlight: Bill Mitchell Products Aluminum LS Engine Block

-

Product Spotlight: Pyramid Optimized Design Sequential Aurora Taillight for 1964½–1966 Mustang

-

PRODUCT SPOTLIGHT: 60-66 Chevy C10 Fresh Air Vent Block Off Plate

-

PRODUCT SPOTLIGHT: Cam Covers for GEN/3 Coyote from Pyramid Optimized Design

HOLLEY CARB TUNING

A Little Help on How to Diagnose—Repair Even—the Holley 4150 Carburetor

Author

Tommy Lee Byrd

Photography: Tommy Lee Byrd & Courtesy of Holley

The Challenge of Tuning a Carbureted Engine

Although it’s not brain surgery, correctly tuning a carbureted engine is no easy task, especially when it comes to upsizing carburetors on high-output engines. There are a lot of elements to be taken into consideration, aside from the carburetor itself, in order to create a happy carburetor environment for your particular engine/chassis application—one that works correctly and has great driveability and an efficient, clean-burning operation. For guys using fuel injection, it’s all about computer knowledge and ensuring that the software is properly optimizing the air/fuel ratio throughout the rpm range. But we don’t have that advantage with a carburetor; we must build it in mechanically so that the carburetor metering systems can do their job at the appropriate times.

The Importance of Holley Carburetors

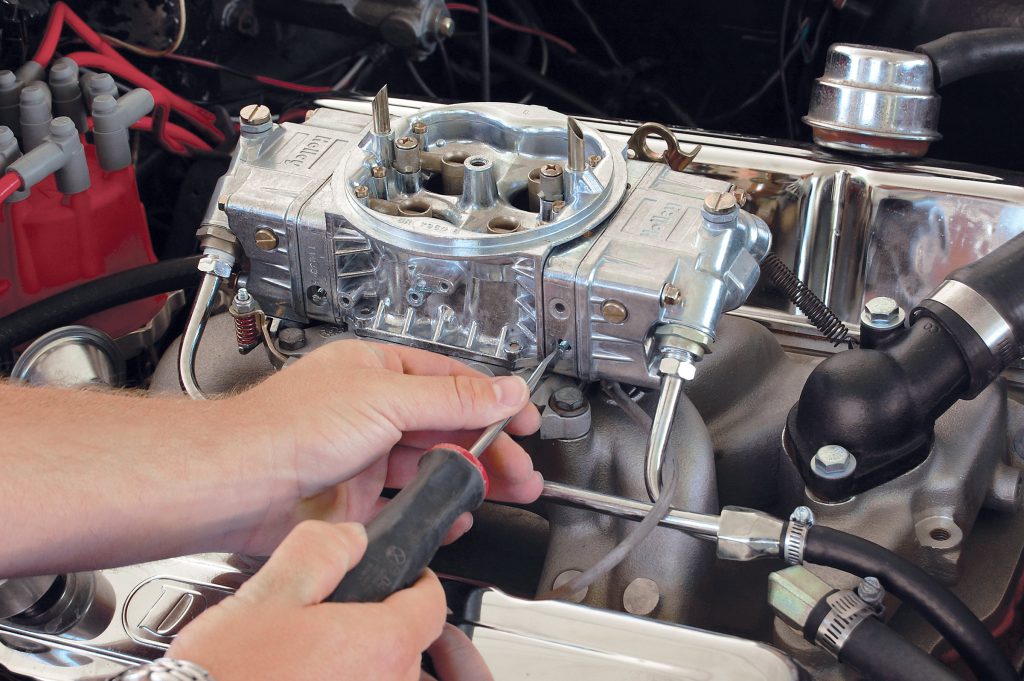

Holley carburetors have long been a staple in the go-fast world of high-performance motoring, whether it’s NASCAR, drag racing, or on the street. Much like other performance-oriented products—perhaps even more so with a carburetor—a carburetor requires a fundamental setup and a degree of maintenance, and that’s considering you have chosen the correct-size carburetor for your application, at least to get it in the ballpark. Knowing how to adjust, maintain, and even repair your Holley carburetor goes a long way toward helping to ensure that your carburetor will make optimum horsepower for a long time. Because of this, we decided to compile a few troubleshooting and repair tips for the popular 4150-series Holley carburetor, which is the series designation for Holley’s street/strip and racing carburetors.

Troubleshooting and Repairing Holley Carburetors

While similar techniques can be used for most Holleys, and to an extent even the race-only Dominator-series carbs, the 4150 Street Avenger is the average street-friendly carburetor most folks prefer. Out of the box, it comes with ballpark tuning and is about as trouble-free as a carburetor can get. But it makes sense to know and understand how to repair one in the event you begin to experience driveability concerns.

Common Issues with Older Holley Carburetors

One of the more common problems with older, used Holley carburetors may well be a lack of cleanliness, both inside and out. This can be caused by a number of things, but if you’re driving an older car with an old gas tank, then sediment from that tank could easily be a source of the problem. This is especially true if filter maintenance has been ignored, or if a quality fuel filter is not incorporated within the fuel delivery system. Picking up sediment usually occurs when a car is run low on fuel or if the car runs completely out of fuel while the electric fuel pump continues to operate. However, an unclean fuel source isn’t the only culprit; dirty fuel lines, a clogged filter and debris in the carburetor fuel-metering system can all upset the fuel/air delivery balance, causing poor performance. You simply cannot expect a carburetor to perform up to expectations if it is not clean or if the fuel is compromised. You also cannot expect that one carburetor that works great on one application will work just as well for a different engine combination, without some slight tailoring that best fits the requirements and/or use of that combination.

The Importance of Carburetor Knowledge

Knowing how to tune a carburetor is a necessary part of owning an older, carbureted car. To help, there are a number of highly regarded experts out there who can do it right the first time, and if necessary they can save you a lot of head-scratching trouble. Even then, if you’re stranded on the highway, or if you’ve traveled to a racetrack with a different altitude, it’s good to know how to tune a Holley carburetor to fit your needs and conditions.

Expert Tips for 4150-Style Carburetors

Take a look at these tips; there may be some small step here that will help you resolve a particular issue. Not all problems need be difficult, but if all else fails, you can always call the folks at Holley. They can walk you through a problem and provide information on rebuilding, tuning, and upgrading your carburetor. Check out the following tips for 4150-style carburetors and see if there’s not something here to help you with your application and setup.

LOADED AT IDLE

Identifying the Problem

Okay, so you bolted on a Holley four-barrel, but every time you pull to a stop, your engine begins to sound like a full-on drag-race engine, even though it is relatively stock, with only a mild camshaft. The engine lopes and snorts along but begins to clear up once it gets into its power band and seems to run fine aside from poor idle quality and spark plugs that foul out prematurely. This is evidence there is an overly rich idling problem.

Simplicity is Key

When dealing with a Holley carburetor, the thing to remember is that simplicity is generally the key to resolving most problems. In this case, the idling problem could be something as simple as adjusting the carburetor idle-mixture screws, which, at idle, could easily result in a “loading up” condition—causing a stumble and hesitation off idle (as the carburetor transitions from the idle circuit to the main metering system).

Inspecting Spark Plugs

To check for proper idle mixture, first inspect the condition of the spark plugs. If the plugs are black, or worse, covered with soot, you have an overly rich idling condition.

Adjusting the Idle-Mixture Screws

If you have a mechanical- or vacuum-secondary, single-accelerator-pump carburetor, there is one idle-mixture screw on each side of the carburetor, since there is only one metering block. On a double-pumper carburetor with two accelerator pumps, there is also a metering block at the rear float bowl, which also features two idle-mixture screws.

Turning the Screws

If you turn the idle-mixture screw in (clockwise), you reduce the amount of fuel delivered to the idle circuit. Backing it out (counterclockwise) provides additional fuel at idle. Generally, carburetor adjustment is a trial-and-error process, but you will be able to tell a difference in idle quality—by the sound of the engine—when you get it close.

Fine-Tuning the Adjustment

Start by turning in each screw one at a time all the way until the engine sounds rough, and back it out slowly until the engine smooths out, perhaps a turn and a half.

THE POWER VALVE MYTH

Occasionally you may hear someone talking about a blown power valve being the cause of bogging or stumbling problems. If you own a Holley carburetor built after 1992, you need not worry about this being the cause, because Holley utilized a check-valve system that completely eliminates the chance of blowing a power valve. Yet there still seems to be a lingering misconception that blowing power valves in a Holley carburetor is a common occurrence—it’s not.

The newer power-valve system consists of a spring, a brass seat and a check ball, and it is 100 percent effective in protecting the power-valve diaphragm from damage due to engine backfire. This system is designed so the power-valve check ball is normally open but quickly seals when a backfire occurs. Once sealed, the check valve interrupts the pressure wave generated by the backfire, thus protecting the diaphragm. However, if you’re convinced the power valve is blown, here’s a little test: At idle, turn the idle-mixture screws all the way in; if the engine dies, the power valve is not blown.

One cause may be an incorrect power valve for your engine/chassis combination. Holley offers a variety of power valves for a wide range of engine loads, from 1.0-inch Hg to 10.5-inch Hg, in both standard-flow and high-flow designs.

FOUR-BARREL BLUES

Checking Secondary Operation

If you have a vacuum-secondary-style Holley carburetor—which, by the way, is arguably the best system for street use—that seems to be bogging, or if the engine feels sluggish at full throttle, as if all four barrels are not opening all the way, you may want to check to ensure that the secondaries are in fact opening. This must be checked under engine load and not by statically revving the engine.

Using the Paper Clip Method

One method Holley suggests to check this is to clip a paper clip on the secondary diaphragm rod, up against the diaphragm housing. Drive the car under full throttle and then stop and check the paper clip. If the clip is lower on the rod, then you know that the secondaries opened and how far. This can also help you determine whether you need a stronger or lighter diaphragm spring.

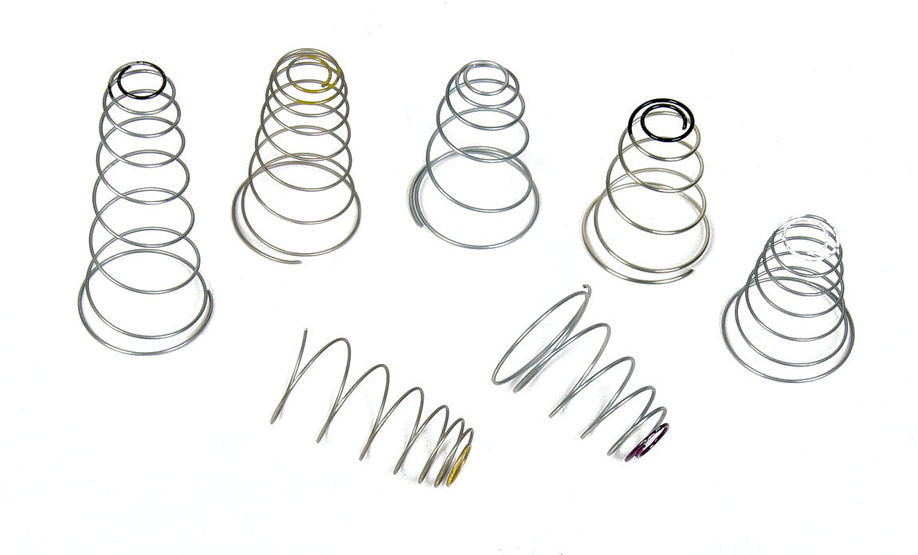

Addressing a Severe Bog

If you are chasing down a severe bog and you have a vacuum-operated secondary 4150, the secondaries may be opening too early. To fix this, Holley offers seven different spring tensions, which will enable you to install a heavier spring. If the secondaries are opening too late, then install a lighter spring.

Influencing Factors

There’s a lot that influences when you need what, and by how much. Your cylinder head and camshaft selection will create a certain engine load, and if the secondary spring is mismatched, the engine can lay down and/or backfire and cough as you stomp the throttle.

Addressing Overly Rich Conditions

Jets, too, can cause an overly rich condition, but that will generally feel more as if the engine is down on power. But when secondary engagement is premature, the engine just can’t burn the fuel fast enough at that engine speed, causing a hesitation and an overly rich condition.

Importance of Secondary Springs

The secondary springs are a key tuning element when tuning a carb to an engine, as overall performance will be determined by how quickly the secondaries engage and the ability of the engine to take the additional fuel/air. While this is a common problem when setting up a carburetor, it’s not at all difficult to get right and establish the proper tuning setup.

COUGHING AND HESITATION

Diagnosing Engine Coughing and Hesitation

Let’s face it: There are many problems that could cause engine coughing and hesitation, which makes it a little difficult to diagnose. Besides idling, however, if the car is moving and continues to stumble, the next place to look is the accelerator pump and its related linkage and components.

Checking the Accelerator Pump

Since the accelerator pump supplies the initial fuel dump off idle, the rate and amount of fuel it delivers are major factors in terms of whether the car stumbles under initial load. First, make sure the pump is working. You can check this by manually operating the accelerator-pump linkage by hand while checking that fuel squirts out of the fuel-discharge nozzles. Also, be sure the pump diaphragm is not torn and that you have a full load of fuel. Too much fuel too early can cause an overly rich condition, and too little fuel too late will cause the car to bog. This can make a huge difference in the application of initial power, so you need to get it right, including the proper-size discharge nozzle.

Adjusting the Accelerator Pump

There is no textbook way to adjust the accelerator pump, but the initial fuel dump is controlled by the accelerator pump itself (diaphragm), the shape of its cam (the actuator), the spring load, the adjustment of the pump linkage (set to 0.015-inch clearance between the lever and the spring rod), and the size of the discharge nozzles. These all play a role in the amount and rate of fuel delivery.

Tuning the Accelerator Pump

For this reason, Holley sells an Accelerator Pump Tuning Kit that includes different diaphragms, pump nozzles, actuator cams, and related pump-assembly parts that will enable you to tune the amount of fuel delivered throughout the accelerator-pump stroke. A proper accelerator-pump setup, along with the correct amount of fuel it will dump, is a remedy for far more than bogging—it’s one of the most critical aspects of properly tuning a Holley carburetor for smooth and powerful initial acceleration.

Considering Jet Size and Secondary Settings

Of course, these same symptoms could also be attributed to incorrect jet size, especially on the primary side. And that’s not to discount secondary settings at wide-open throttle, as a mechanical or vacuum secondary is also important for full-throttle blasts. This is less of a concern at normal fuel delivery because a smooth, steady throttle application will not load the engine.

Monitoring Spark Plugs

Keep a close watch on the spark plugs to monitor how the fuel is burning (spark plug color), and you will be able to more accurately judge how to adjust the accelerator pump(s), the primary, and the secondary fuel transition and metering.

FLOATS 101

Whether you’re bolting on a new Holley or tuning an old swap-meet carburetor, it’s a good idea to adjust the float level and the front and rear bowls. The floats can be adjusted in dry or wet configurations, with wet being the more convenient for on-car tuning. First, start the engine and allow it to idle on its own before shutting it off and removing the sight plug on the side of the fuel bowl. Now inspect the fuel level in the bowl and adjust accordingly. Generally, if the fuel level is just under the plug threads, the floats are adjusted correctly. Remember, a quarter turn on the adjustment nut should give you a noticeable change if you have a rich or lean condition. Turning the adjustment nut clockwise lowers the float level, while spinning it counterclockwise raises the float.

Also, if you’re running a blow-through power-adder, such as a turbocharger or centrifugal supercharger, it’s very important to prepare your carburetor accordingly. To withstand the additional pressures, plastic or brass floats must be exchanged for nitrophyl floats, which will not collapse under boost. Also remember that nitrophyl floats require a little lower fuel level to run correctly, but this is another trial-and-error process until you get it right for your engine and chassis. Always keep a few shop rags handy when adjusting float levels, and do not allow fuel to puddle on the intake manifold. We don’t have to tell you that fuel is flammable.

DIRT AND FUEL DON’T MIX

The Importance of Cleaning a Holley Carburetor

Well, actually, dirt and fuel will mix, but the result is never desirable. Sometimes all a Holley carburetor needs is a good cleaning to solve a few basic problems, so there is such a thing as a quick fix in the carburetor world.

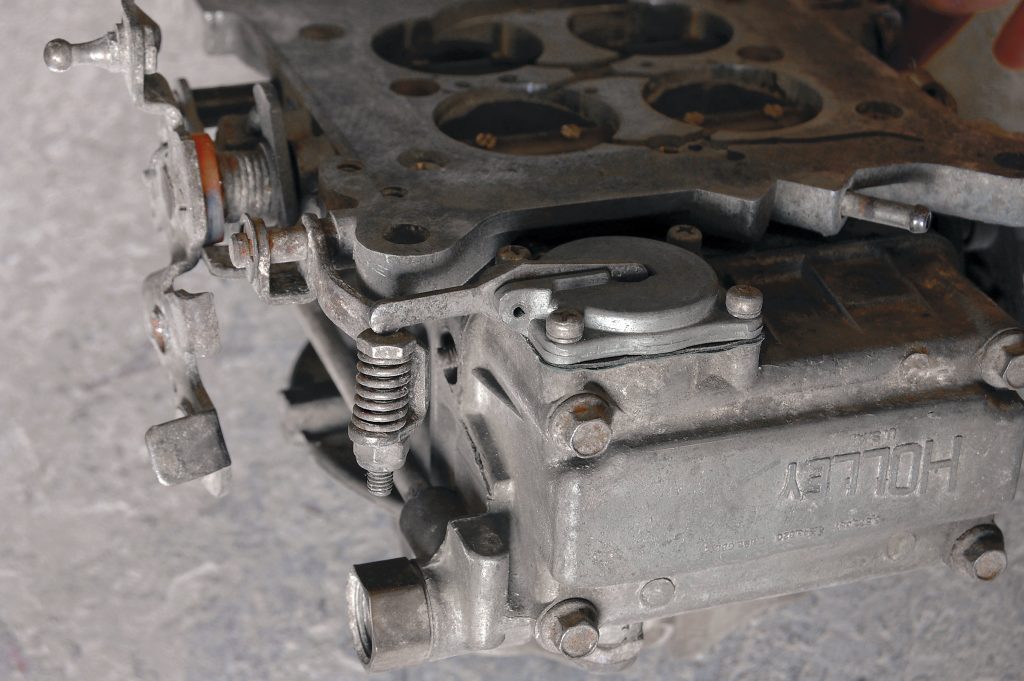

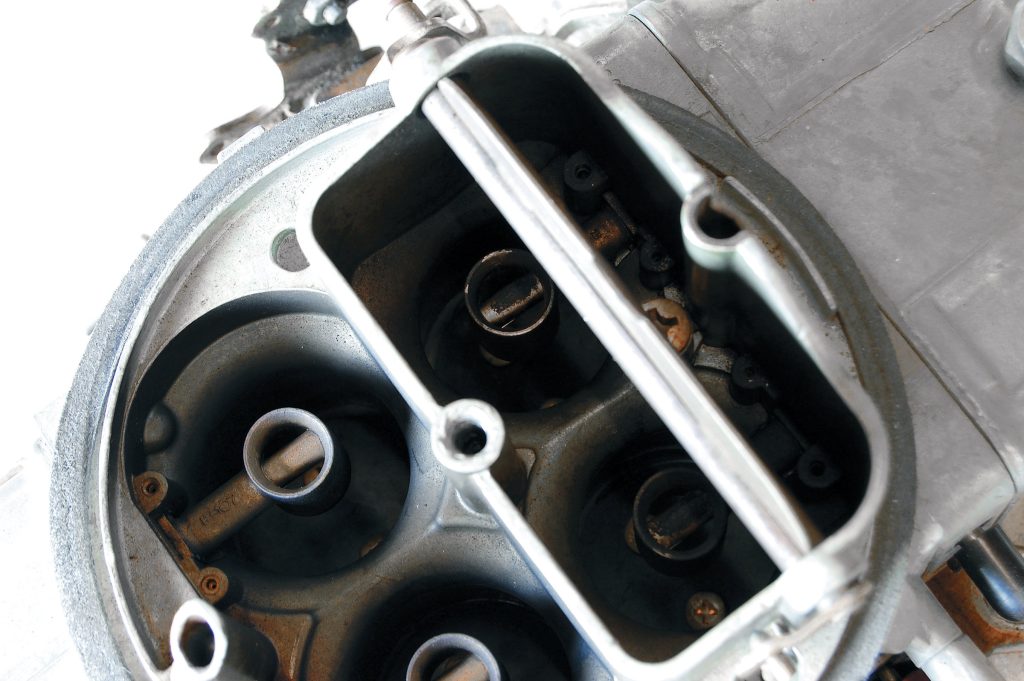

Recognizing the Need for a Rebuild

This 750cfm Holley has served many years as a good carburetor, but it’s time for a rebuild and a thorough cleaning. You can see the dirt that has collected on the topside, and if there’s dirt here, the internals need to be cleaned as well.

Cleaning and Rebuilding the Carburetor

The simplest remedy is to buy a rebuild kit, disassemble the carburetor, and let it soak overnight before reassembling it. Symptoms of a dirty carburetor consist of (but are not limited to) a rich condition, especially at idle, thanks to trash in the float-needle-and-seat area, causing it to overflow.

Consequences of a Dirty Carburetor

This can also result in a continuous flow of fuel even when the throttle is closed—a condition that could wash down the cylinder walls with gas, ruining rings and turning the oil into a thin lubricant, all of which is bad news.

A COMPLETE JET SET

Adjusting Fuel Delivery with Different Jets

If you find that your engine is starving for fuel or has too much fuel, the easiest way to adjust fuel delivery is with a different set of jets.

Investing in a Holley Jet Kit

Holley makes this jet kit, which features a wide variety of jet sizes, from No. 64 to No. 99, and it’s a good investment if you plan to dyno-tune or spend time tuning your engine.

Importance of Proper Jet Selection

It is absolutely essential if you race the car in varying climates or at different altitudes. Jet sizes are self-explanatory, but you must be careful not to create an overly lean condition, where fuel starvation comes into play, as that can result in a serious potential for engine damage.

FIND THE RIGHT CARB FOR YOUR APPLICATION

Choosing the Right Carburetor Size

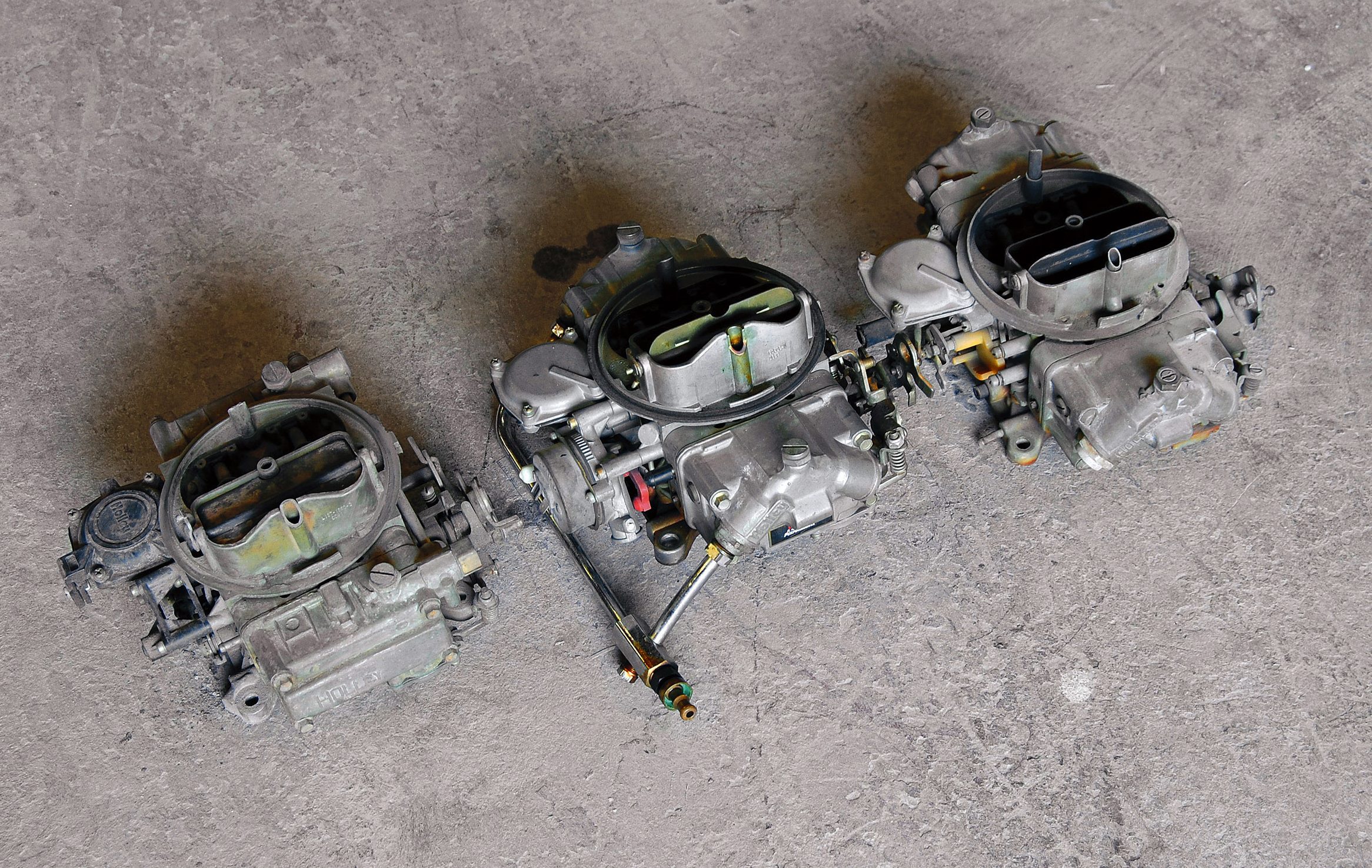

Holley offers many carburetors in all sizes to fit a number of different applications, including those designed specifically for the street. However, making the right selection can be a little tricky because it is common to over-carb your engine (too much cfm for the engine size).

Carburetor Options for Stock Engines

For you Ford folks, don’t laugh, but if your engine is relatively stock, you may find increased street performance simply by using a two-barrel carb, such as a Holley 2300. Stock Ford engines have relatively small valves, which makes over-carburetion almost a given. A five-liter engine that revs to, say, 6,000 rpm may comfortably use a 500cfm two-barrel, and for smaller stock engines there is also a 350cfm two-barrel Holley.

Expanding Horizons with Four-Barrel Carburetors

Beyond this, the horizons expand rather dramatically when you get into four-barrel carburetors, and those selections are best served matching carburetor cfm with the engine modifications—size, cam timing, cylinder head flow, and intended rpm use.

Holley 4150 Street/Strip HP Series

But for the street and strip, it’s hard to beat the new Holley 4150 Street/Strip HP series of carburetors, available in 650- and 750cfm. The 4150 650cfm is a mechanical-secondary double-pumper-style carburetor with no choke. The 4150 750cfm carburetor is available in either vacuum-secondary or mechanical-secondary design (PN 82750 or 82751, respectively). And while engine size and rpm range will dictate which carb is best, as a rule of thumb, with a 350ci small block, a 6,000rpm engine might be best suited with a PN 2651 650cfm 4150 carb, and a higher-output engine of the same displacement capable of revving to 6,500-7,500 rpm would be better suited with a 750cfm version, with either vacuum or mechanical secondaries.

Race-Style Carburetors for High-Output Engines

And if you have a high-output engine with high compression and lots of high-revving cam timing, you may wish to consider one of the many race-style Holley carbs, which are available as large as 1,000 cfm. In fact, the 4150 HP-series four-barrel is available in 390-, 600-, 650-, 750-, 830-, 950- and 1,000cfm versions, all with mechanical secondaries. For lots of engine displacement, there’s the square-bore Holley Dominator series, available in 750-, 1,050- and 1,150cfm, in single- or dual-carb configurations and with two- or three-circuit metering. With these carburetors it’s about all-out performance, so matching the carb to the engine is much more a matter of engine displacement, engine airflow and optimum rpm, which means 9,500 rpm is not beyond the scope of where these carburetors are expected to work.

ARTICLE SOURCES

Holley Performance

1801 Russellville Rd.

Bowling Green, KY 42101

270/782-2900