THE AUTO BUILDER

Featured

- All Post

- 20 High Priority - SR Super Rod

- Builds

- 25 High Priority - FB Ford Builder

- Cars

- 30 High Priority - AR American Rodder

- 01 Post Status

- 35 High Priority - RD Rodders Digest

- 40 High Priority - OTR On the Road

- 45 High Priority - SRB Street Rod Builder

- 50 High Priority - TB Truck Builder

- 55 High Priority - BSCENE Buckaroo Scene

- 60 High Priority - FPB Family Power Boat

- Trucks

- Swaps

- Performance Boats

- _000 Home Sliders

- Modern/Future Tech

- Builders

- 00 Sidebars

- Manufacturers

- 05 High Priority - HCI Hot Compact Imports

- 05 Publications

- 10 High Priority - CR Chevy Rumble

- Back

- Fuel System

- Electrical

- Exhaust

- Transmission / Drivetrain

- Suspension

- Steering

- Brakes

- Wheels and Tires

- Interior

- Exterior

- Accessories

- Chassis

- Engine

- Power Adders

- Back

- Transmission / Drivetrain

- Suspension

- Steering

- Brakes

- Wheels and Tires

- Interior

- Exterior

- Accessories

- Chassis

- Engine

- Fuel System

- Power Adders

- Electrical

- Exhaust

- Back

- Brakes

- Wheels and Tires

- Interior

- Exterior

- Accessories

- Chassis

- Engine

- Electrical

- Exhaust

- Fuel System

- Transmission / Drivetrain

- Suspension

- Power Adders

- Steering

- Back

- Exterior

- Accessories

- Power Adders

- Chassis

- Engine

- Electrical

- Exhaust

- Fuel System

- Transmission / Drivetrain

- Suspension

- Steering

- Brakes

- Wheels and Tires

- Interior

- Back

- Engine

- Fuel System

- Electrical

- Power Adders

- Exhaust

- Transmission / Drivetrain

- Suspension

- Steering

- Brakes

- Wheels and Tires

- Interior

- Exterior

- Accessories

- Chassis

- Back

- Fuel System

- Electrical

- Exhaust

- Transmission / Drivetrain

- Power Adders

- Suspension

- Steering

- Brakes

- Wheels and Tires

- Interior

- Exterior

- Accessories

- Chassis

- Engine

- Back

- Transmission / Drivetrain

- Suspension

- Steering

- Brakes

- Wheels and Tires

- Power Adders

- Interior

- Exterior

- Accessories

- Chassis

- Engine

- Fuel System

- Electrical

- Exhaust

- Back

- Steering

- Interior

- Accessories

- Power Adders

- Exterior and Hull

- Engine

- Fuel System

- Electrical

- Outdrives

- Back

- Power Adders

- Chassis

- Engine

- Electrical

- Exhaust

- Fuel System

- Transmission / Drivetrain

- Suspension

- Steering

- Brakes

- Wheels and Tires

- Interior

- Exterior

- Accessories

- Back

- Chrysler

- Mercury

- Subaru

- Volvo

- Volkswagen

- Chevrolet

- Cadillac

- Pontiac

- GMC

- AMC

- BMW

- Oldsmobile

- Buick

- Jeep

- Acura

- Lincoln

- Mitsubishi

- Ford

- Dodge

- Honda

- Nissan

- Toyota

- Plymouth

- Back

- 05 Pub HCI Hot Compact Imports

- 15 Pub 4x4 4x4 Builder

- 20 Pub SR Super Rod

- 25 Pub FB Ford Builder

- 30 Pub AR American Rodder

- 35 Pub RD Rodders Digest

- 40 Pub OTR On the Road

- 55 Pub BSCENE Buckaroo Scene

- 10 Pub CR Chevy Rumble

- 50 Pub TB Truck Builder

- 60 Pub FPB Family Power Boat

- 45 Pub SRB Street Rod Builder

- Back

- Steve Sellers

- Bobby Alloway

- Chip Foose

- Boyd Coddington

- Rad Rides by Troy

- Cal Auto Creations

- Ring Brothers

- George Barris

- Jesse James

- West Coast Customs

- Jack Fuller

- Carl Casper

- Bob Cullipher

- J.F. Launier

- Jerry Nichols

- Back

- Street Rods

- Hot Rods

- Late Model

- Drag Race

- Handling

- Compact Cars

- Fuel System

- Electrical

- Exhaust

- Transmission / Drivetrain

- Suspension

- Steering

- Brakes

- Wheels and Tires

- Interior

- Exterior

- Accessories

- Chassis

- Engine

- Power Adders

- Transmission / Drivetrain

- Suspension

- Steering

- Brakes

- Wheels and Tires

- Interior

- Exterior

- Accessories

- Chassis

- Engine

- Fuel System

- Power Adders

- Electrical

- Exhaust

- Brakes

- Wheels and Tires

- Interior

- Exterior

- Accessories

- Chassis

- Engine

- Electrical

- Exhaust

- Fuel System

- Transmission / Drivetrain

- Suspension

- Power Adders

- Steering

- Exterior

- Accessories

- Power Adders

- Chassis

- Engine

- Electrical

- Exhaust

- Fuel System

- Transmission / Drivetrain

- Suspension

- Steering

- Brakes

- Wheels and Tires

- Interior

- Power Adders

- Chassis

- Engine

- Electrical

- Exhaust

- Fuel System

- Transmission / Drivetrain

- Suspension

- Steering

- Brakes

- Wheels and Tires

- Interior

- Exterior

- Accessories

- Engine

- Fuel System

- Electrical

- Power Adders

- Exhaust

- Transmission / Drivetrain

- Suspension

- Steering

- Brakes

- Wheels and Tires

- Interior

- Exterior

- Accessories

- Chassis

- Back

- 05 Post Imported

- 20 Post Missing Images (All)

- 25 Post Missing Images (Partial)

- 15 Post In Progress

- 30 Post Internal Review

- 40 Post On Hold

- 27 Post Missing Content

- 50 Post Approved

- 10 Post Images Imported

- 17 Post Missing TXT Files

- 18 Post Missing PDF Files

- Back

- Chassis

- Engine Swaps

- Interior Swaps

- Driveline

- Back

- Street Trucks

- OffRoad Trucks

- Fuel System

- Electrical

- Exhaust

- Transmission / Drivetrain

- Power Adders

- Suspension

- Steering

- Brakes

- Wheels and Tires

- Interior

- Exterior

- Accessories

- Chassis

- Engine

- Transmission / Drivetrain

- Suspension

- Steering

- Brakes

- Wheels and Tires

- Power Adders

- Interior

- Exterior

- Accessories

- Chassis

- Engine

- Fuel System

- Electrical

- Exhaust

- Back

- 01 Sidebar Left

- 01 Sidebar Right

Spotlighter

POPULAR READS

-

Product Spotlight: Bill Mitchell Products Aluminum LS Engine Block

-

Product Spotlight: Pyramid Optimized Design Sequential Aurora Taillight for 1964½–1966 Mustang

-

PRODUCT SPOTLIGHT: 60-66 Chevy C10 Fresh Air Vent Block Off Plate

-

PRODUCT SPOTLIGHT: Cam Covers for GEN/3 Coyote from Pyramid Optimized Design

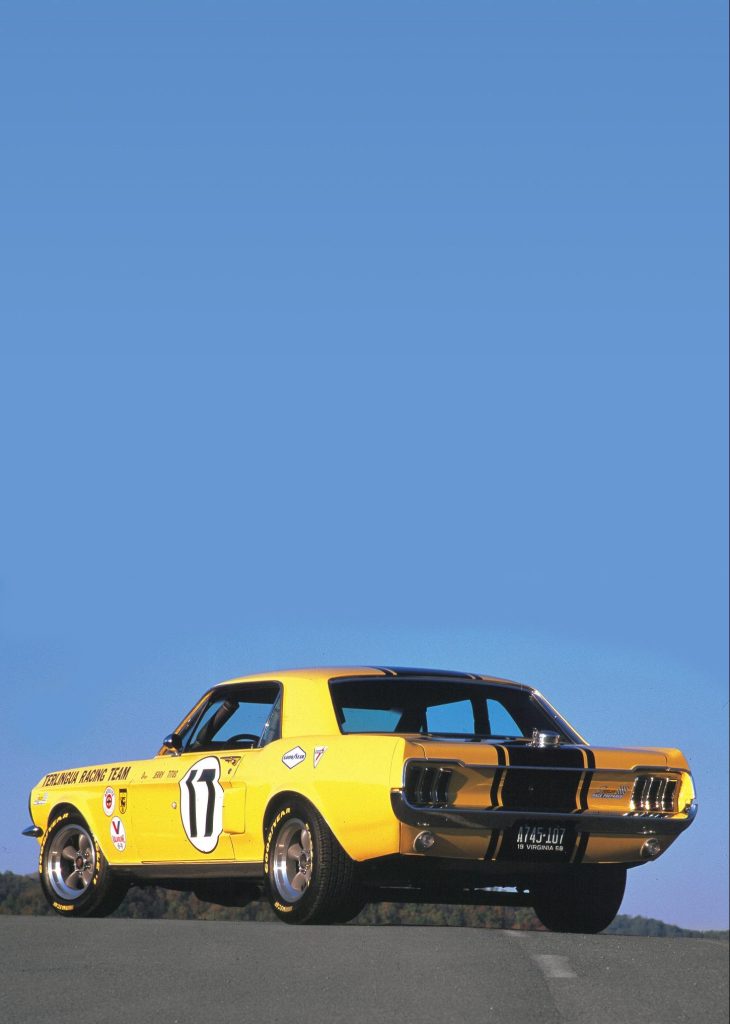

TERLINGUA TERROR

Michael Akers Has a Blast in His SCCA Tribute

Author

Brad Ocock

Story & Photography

Now that’s the way to start a story! We’d just love it if those were the first few words out of more people’s mouths when we compliment them on the looks of their cars. You might say Lebanon, Virginia’s Michael Akers is Mustang guy. With a stable of ponies, including a ’66 convertible, a ’68 convertible, a ’71 Mach 1, a ’72 Mach 1 and a ’68 GT500KR, there’s no question he bleeds Ford Blue. Yet, with this impressive herd, it is this car, which he built with “stuff” just lying around, that he chose to drive to Year One’s Bristol Bash.

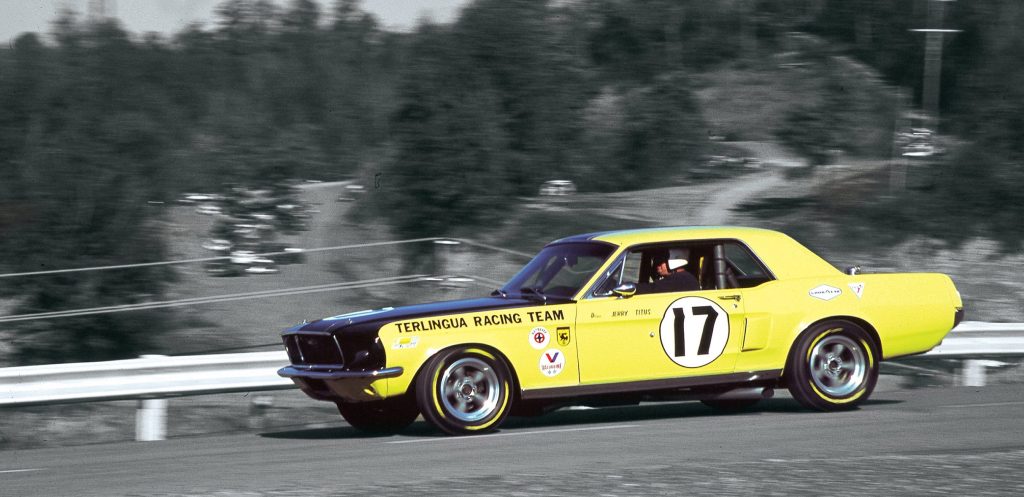

No, it’s not the genuine article—a real Shelby-prepped, Jerry Titus-driven Mustang campaigned in the SCCA series in the late ’60s—but that really doesn’t make it any less meaningful or take anything away from it. In fact, to our way of thinking (and Akers’, too, judging by the miles he’s already put on it), that just makes it all the more fun. “It’s a tribute to Jerry Titus’ 1967 Trans-Am championship, and all the other great drivers and teams of that time,” Akers told us.

The car started out as nothing but a body shell with rusty quarters, but there’s still some pedigree here. “The heads are off an engine Parnelli Jones once ran, and it has Gapp and Roush pistons. The intake is an early Holman-Moody piece, and the oil filter relocation kit is also from Holman-Moody.” And then there are the little “in the spirit” details, such as the dash insert constructed from an old stop sign, because Akers made do with what he had on hand, not unlike most racers of the day. Although the car is definitely true to the spirit of SCCA competition, some concessions also had to be made—this one wears bumpers because he couldn’t get it registered to drive on the street without them, and once on the street, Polyglas tires wouldn’t be nearly as much fun as modern rubber.

While vintage race goodies top the engine, the short block is another concession, with the modern Bud Moore R302 cylinder block poured in 2002. An Eagle crank and heavy-duty H-beam rods swing the Gapp and Roush 13.5:1 pistons, with a special Comp Cams cam running the valve gear in the old Trans-Am-spec heads. “It’s old technology, and what’s available today is better,” Akers says of the heads and high-compression pistons. But hey, as much as we love well-tuned modern power running on pump gas, sometimes pedigree trumps practicality, and this is unquestionably one of those times. In a class that gave us 3×2 intakes from Ford and Chrysler, and the Camaro 2×4 cross-ram, Akers’ induction system is fairly tame by comparison. The vintage Holman-Moody intake is a single 4-bbl intake, topped with a Holley double-pumper and chrome open-element air filter.

After first glancing at the engine, we thought something was, well, different. We even briefly wondered if it was a big block. Then we noticed the extra-tall valve covers, and that’s what was throwing us. Akers saved our automotive dignity when he said that it’s happened before. The tall valve covers make the engine look much wider because there’s very little room between them and the inner fenders. The “import” bar tying the shock towers together makes the engine bay look even more cramped than a Mustang usually does. The special valve covers were reported to have come from Gapp and Roush, and they’re simply two covers spliced together, with the top of one and the bottom of the other cut off and stacked, making a double-tall piece to clear the high-lift cams and rocker-arm girdles that teams ran back in the day. We’ve often thought this would be a cool modification on the right kind of car, and seeing it done confirms our opinion. A vintage Cobra cast-aluminum oil pan, a modern MSD distributor and Hooker headers finish off the engine. The old-technology heads and pistons dyno’d 425 hp at an “easy 8,000 rpm,” Akers reports. There’s no doubt that a cam swap would realize more power from those 13.5:1 pistons, old heads and intake without modifying the authentic hardware, but then he couldn’t drive it on the street, which he does often.

Backing the small block is a Centerforce clutch and Lakewood blow-proof bell housing mounting up a late-model Tremec five-speed shifted by Hurst—another subtle concession to street driving. At the other end of the driveshaft is a 9-inch rear with 3.70 gears and a Detroit Locker differential. Stock HP leaf springs and Koni shocks suspend the rear, while the front suspension is a mix of 1-inch lowering spindles, pro-rate coil springs, 1-inch relocated upper control arms and a big front sway bar. Stock Ford brakes are found at the four corners, drums in back, discs up front. There really was no other option when it came to rolling stock—American Racing Torq-Thrusts were the wheels of choice on Trans-Am racers, and they’re found on Akers’ car, too, in a relatively mild 15×7 size with Goodyear 215 and 235 tires.

When Titus took the title in 1967, the cars were virtual stockers, with many of the same kinds of mechanical improvements we make to our daily drivers today. The interior of Akers’ car accurately reflects the competition interior on the original, where we find a full backseat, headliner and passenger-side front bucket, with a fiberglass racing bucket for the driver. The factory door panels and dash pad also were retained, while the original gauge cluster was replaced with a flat sheetmetal panel (fabricated from the aforementioned retired stop sign) filled with Stewart Warner gauges. The small factory rubber foot-pedal pads were also swapped out for larger sheetmetal pieces to make heel-toe cornering easier, and a full rollcage and fire extinguisher finish out the interior.

Fortunately for Akers, the Titus car was a notch-back, not the more popular—and therefore more expensive—fastback, which allowed him to get a bare ’68 body shell at a more reasonable price. It also doesn’t hurt that Mustangs are about the most popular cars in terms of parts availability, with new hoods, fenders, complete doors, fresh bumper stampings and just about anything else you’d need to build one being available from any number of suppliers. Between that and his own collection of leftover parts from previous restorations, the car came together pretty quickly—only three months. Major bodywork included replacing the lower section of both quarter panels and slightly flaring the wheel openings, with Shelby quarter-panel brake scoops added, while the rest of the body was left pretty much alone. We found the round, chromed bezels in the center of both doors interesting. They’re located just ahead of the white circles carrying the number 17, and rear license plate lights are used to illuminate the car’s number during night competition.

The trunk area received a fair amount of competition-correct detail, with an oversized extra-capacity gas tank and pit-stop quick-fill gas cap poking through the decklid. Early Mustang gas tanks are an integral part of the trunk floor, with the top panel of the tank being the actual trunk floor. This top panel has a wide flange all the way around it to provide an area to spot-weld the tank to the floor, with the sides and bottom of the tank hanging below the floor. Back in the days before crash-friendly fuel cells, the competition tank was simply the bottom half of one tank flipped upside down and welded to the top side of another tank, with the flange left intact to weld it into the trunk floor. A filler neck was welded to what was now the top of the new tank and topped with a Cobra-style gas cap that pokes through the trunk lid. The original competition cars didn’t have the sheetmetal surround around the cap. Akers created that from an old “No U-Turn” sign (“because I was out of stop signs”) and added a gasket to the underside of the decklid to keep water out of the trunk. A reproduction Autolite battery mounted behind the wheel well on the passenger side finishes the trunk’s interior, and a single hood pin in place of the stock latch mechanism keeps the lid closed. The race tank and filler neck make carrying luggage or anything else almost an impossibility, but there’s no doubt it completes the competition feel of the vehicle.

The car was finished in May 2001, and since then Akers has had a blast driving it, putting thousands of miles on the odometer, even though creature comforts such as power steering, power brakes and A/C are nonexistent. “I had a radio in it, but I couldn’t hear it,” Akers said, so it came out, leaving nothing but gears, brakes and throttle to keep the driver occupied. What a blast! It’s no wonder this pony gets out of the barn to run so often.

Just What Is a Terlingua?

We wondered what exactly a “Terlingua” is, and why it’s a terror. A little searching on the Internet located a couple of Shelby websites that gave us our answer.

It seems that in the early ’60s, Carroll Shelby and a friend bought about 200,000 acres in the southwest part of Texas near Big Bend National Park and the Mexican border. Before Texas was part of the U.S., three Indian tribes—Comanche, Kiowa and Apache—used the area to stage raiding parties, and it became known as Tres Linguas, or Three Languages, which our melting pot eventually boiled down to “Terlingua.” In the days of the Silver Rush, the town of Terlingua had a population of about 5,000, but today it is a ghost town.

A friend of Shelby’s drew up a medieval-style crest to represent Terlingua, with an old-English-style drawing of a lion-looking rabbit as the central image, because desert hares are plentiful in the area. Three feathers are below the rabbit to represent the three tribes, and “1860” is in the upper left corner to represent a horse-drawn wagon race that occurred in 1860. The Terlingua Racing Team was born, and the crest appeared on Shelby-prepped cars, including Parnelli Jones’ King Cobra at the ’64 LA Times Grand Prix, four Indy 500 winners, cars at Le Mans, Sebring, Riverside, Laguna Seca, and the Trans-Am Mustangs raced in 1967 and 1968. It would probably be fitting to consider the cars wearing the Terlingua crest as a Yankee snub to the pretentious factory-backed European sports cars that the Shelby teams competed against—and beat.

Eventually, Shelby and friends set up a Terlingua city council, with council meetings being held at a bar or restaurant in Dallas. In 1967, Shelby held a chili cook-off, which has since taken on a life of its own. Today, the annual CASI (Chili Appreciation Society International) Chili Festival is held in November and is the premier event for chili aficionados.