Street Rods

There was a time not all that long ago, between station wagons and SUVs, when big conversion vans were the family transportation of choice. In the beginning, the Big Three considered vans to be commercial vehicles, fitted with rubber floor mats, vinyl seats and short (if any) side windows, not the decked-out, posh family transport they would become.

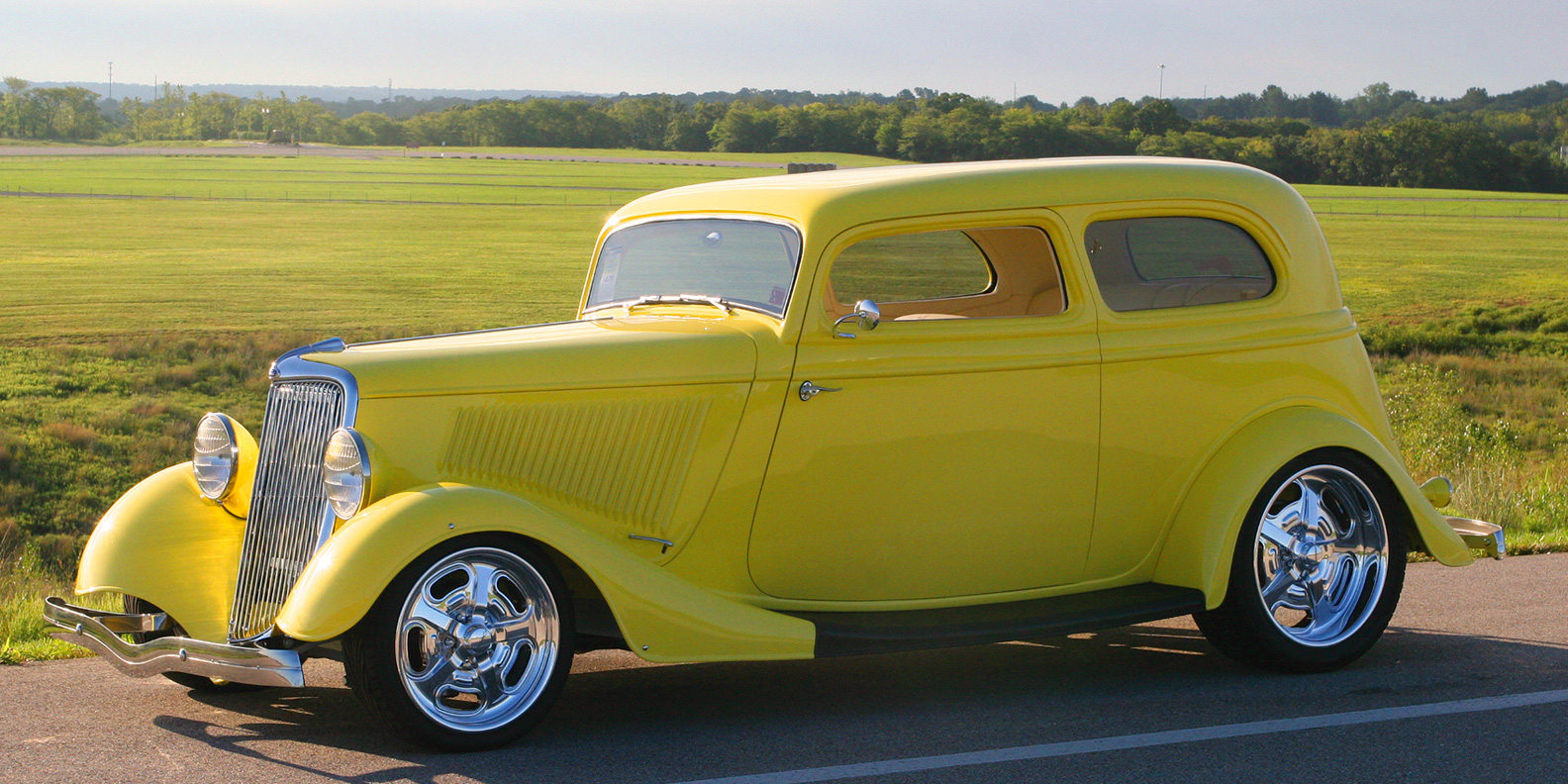

We know youʼve already checked out the photos or you wouldnʼt be reading this. You obviously wish to know a little more about this jack, so weʼll cut to the bottom line: If you get one of these for your very own, youʼd better not tell any of your buddies about it, or you will have to make room in the safe to store it. If they spot it in your trunk, just laugh about how you got it as a gift and hope none of them reads this article, or you will have to tape a cell phone to it to find out where it is this weekend–just when you need it!

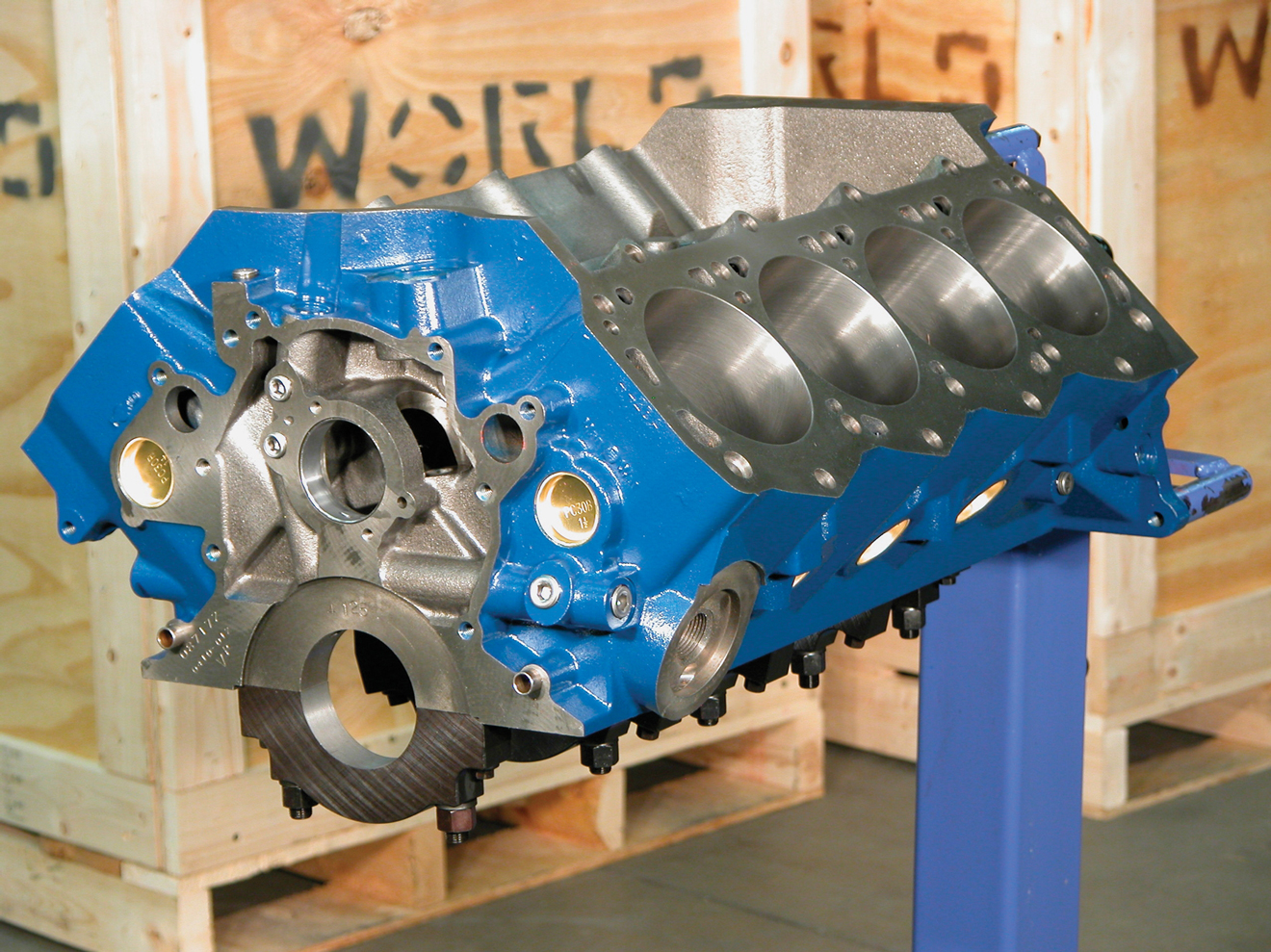

While the small-block Chevy is the popular engine choice for many enthusiasts, many are now relying on a Blue Oval heart for their performance bodies. With its link to Ford, the original body manufacturer for many of the classic cars we see today, the small-block Windsor-style Ford engine offers several advantages. When compared to Chevy, the lack of firewall clearance for a number of Chevy engine swaps is due to the rear distributor position of the engine. The front-mount distributor position is the more logical place to drive the distributor and the oil pump. Not to mention, it’s much more convenient.

The Specialty Equipment Market Association (SEMA) Show engulfs Fabulous Las Vegas annually. It brings together the biggest names in the automotive world to show off the latest and greatest, whether it’s new products, amazing custom builds, or the newest trends. TheAutoBuilder is excited to be in the thick of it all.

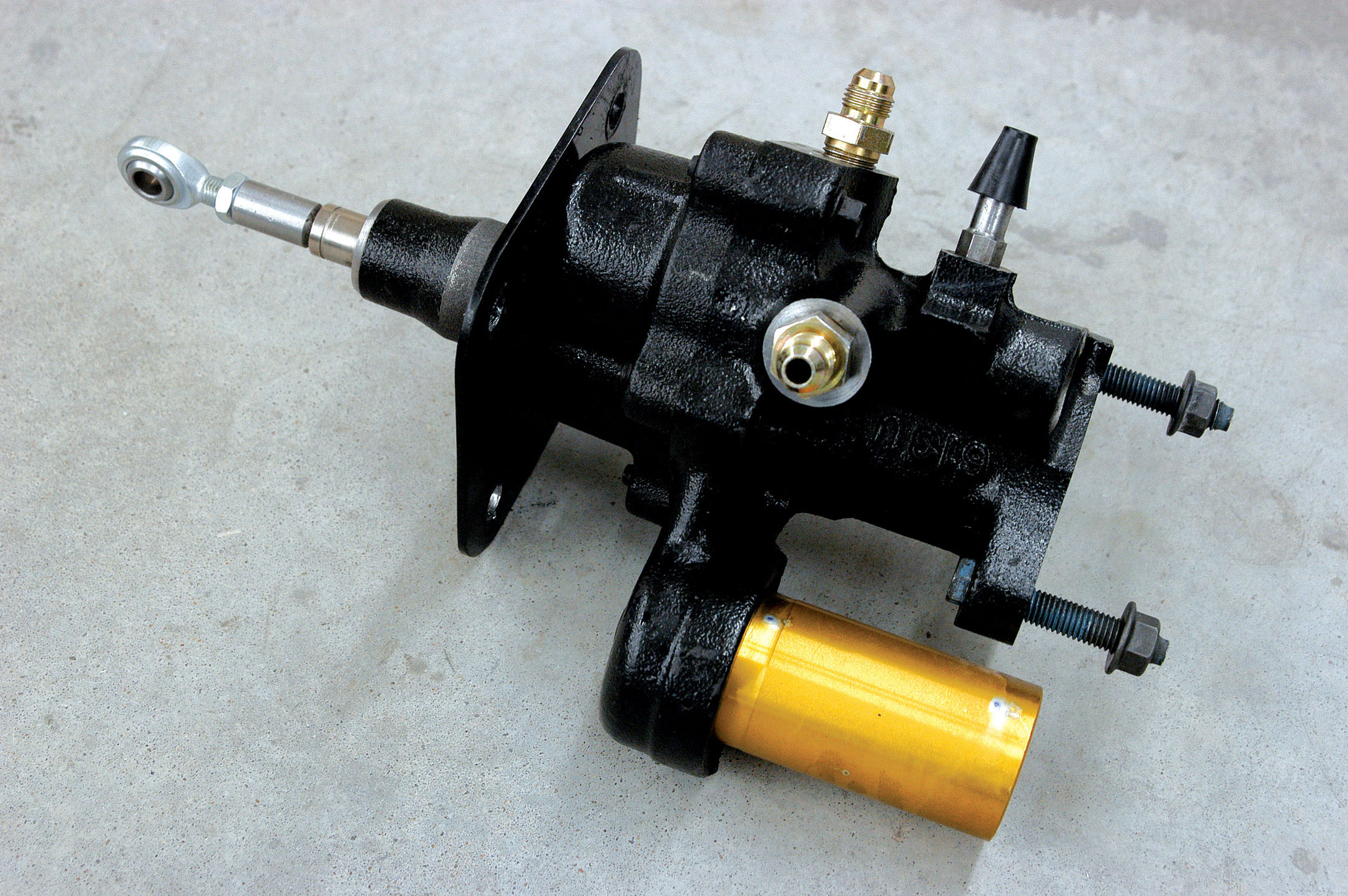

Nothing is more terrifying than cruising down the street to the fairgrounds when some idiot pulls out in front of you and you have to jump on the binders. Making a panic stop can be difficult when you are trying to stop 800 throbbing horsepower with a set of 9-inch rotors and single-piston calipers. You might even wonder if it will stop as you mash the brake pedal. When it comes to street rods with big motors, one braking concern is vacuum pressure. Is there enough? Many high-performance camshafts add power to the motor but produce low vacuum levels. This is something to consider when selecting your engine components. Of course, if the motor fails, you will have no vacuum, so stopping will be a real problem.

Unlike a regular car door, the back door of a sedan delivery is often left open for loading, unloading and so on. With nothing to hold it open, the slightest breeze will slam it because when a delivery is dumped in the front as ours is, gravity lends a heavy hand to the slam. We’ve never been knocked unconscious, but we’ve suffered some nasty lumps on the noggin. Worse yet, with no mechanism but the hinges, you never hear or see it coming.

There are many reasons why the icon cars have achieved the lofty status they now enjoy, but one of the more obvious reasons is the simple fact that they were finished. Their existence and subsequent high-level exposure have inspired many a young lad to undertake similar projects, and for every famous car built in the early years, probably two others were started in an attempt to either copy or outdo it, but they never saw the light of day.