Exterior

We all know itʼs what lies beneath the paint that really matters—a good chassis, great metalwork, and great design. Yet, having said that, the paint job still remains the single most important element of any rod or custom. After all, even if the groundwork has been laid, your bodywork is straight and great, your design is fine and your mechanicals are flawless, a poor paint job can spoil it all.

When starting any project that requires bodywork, rebuilding or even repainting, the first question is always, “What could possibly be lurking under the old paint that could come back and haunt us later?”

The lines of ’55-’57 Chevys are almost sacrosanct. They haven’t been modified or changed over the years with very good results. There have been a couple of exceptions, but by and large, chopped tops, restyled fenders and other modifications that alter their original lines don’t come off looking real good. The problem is in the proportions. We’re not sure if it’s because the factory got them so perfect right out of the gate, or if it’s that most have been left alone over the last 50 years, so a chopped top looks strange. Whatever the reason, the classic “greenhouse” roofline, long fenders and slab sides all work very well together.

Now, it may seem crazy that anyone would take sandpaper to a new paint job, but if you want to have a glass-like finish that is exactly what happens. Of course, it is special sandpaper, and the person doing the work needs to know exactly what he is doing or that paint job can be toast. One of the things that makes color sanding possible is that the paper used is meant to be wet while the job is taking place. The water not only works as a lubricant, but it also removes the fine paint sludge from the area. The problem is getting that water in the proper place and having enough of it to do the job. After all, who really likes sticking his arm into a cold bucket of water time after time?

Have you ever looked at another enthusiast’s ride and noticed something unique, yet very clever, that made the vehicle stand out or perform better and thought, “Why didn’t I think of that?” Well, we’ve done some of the homework, legwork and research to provide you with a similar advantage. We scoured the tuning shops and interrogated the pros to find out what tips they have done that our readers could apply to their own vehicles.

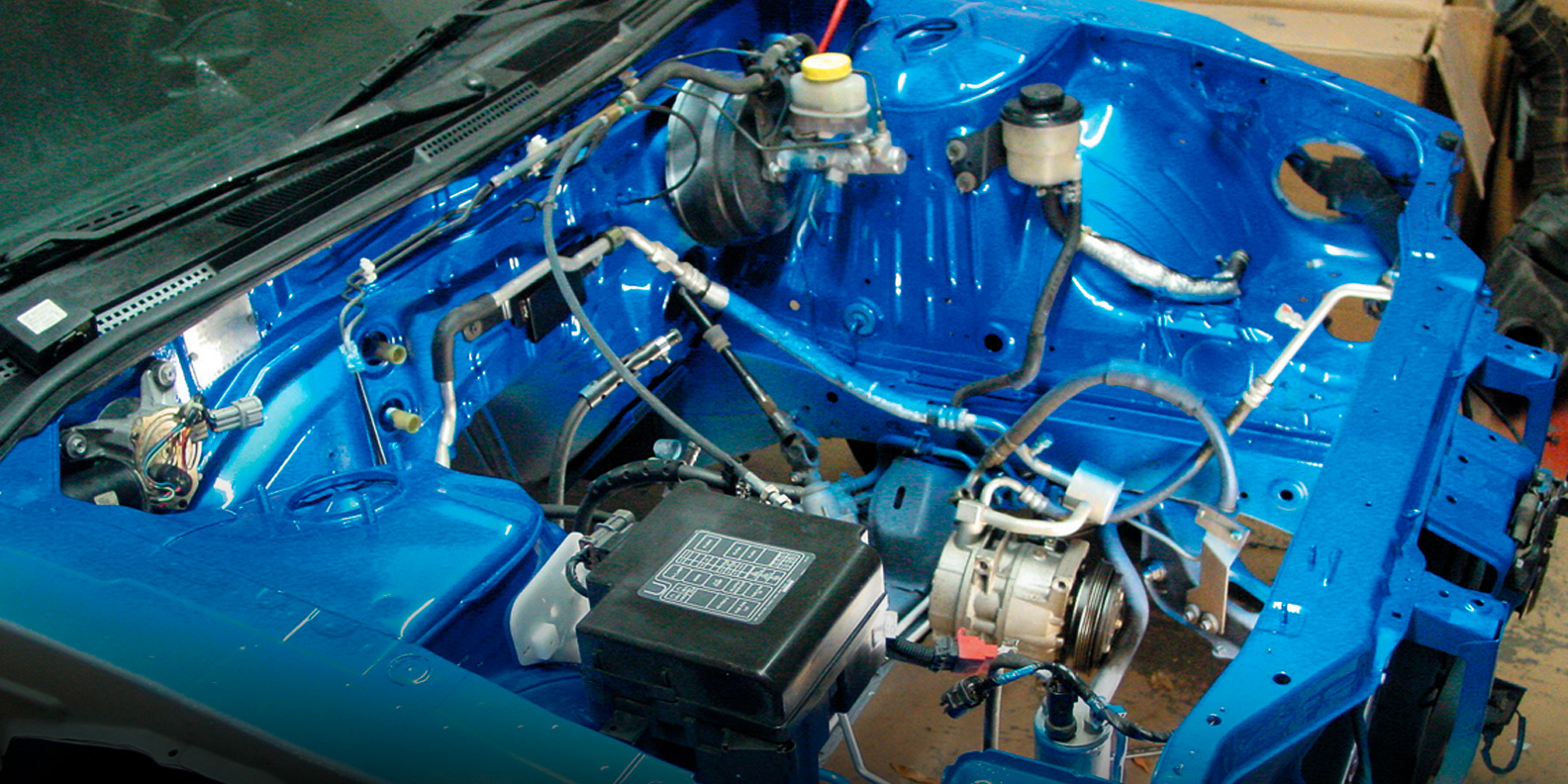

We learned that Underground Motorsports in Little Rock, Arkansas, was going to build one fast daily driver, so we thought we’d take a peek and drop some knowledge for you. We were looking for any tech procedures that may illustrate for readers how a car of this sort is built from scratch.

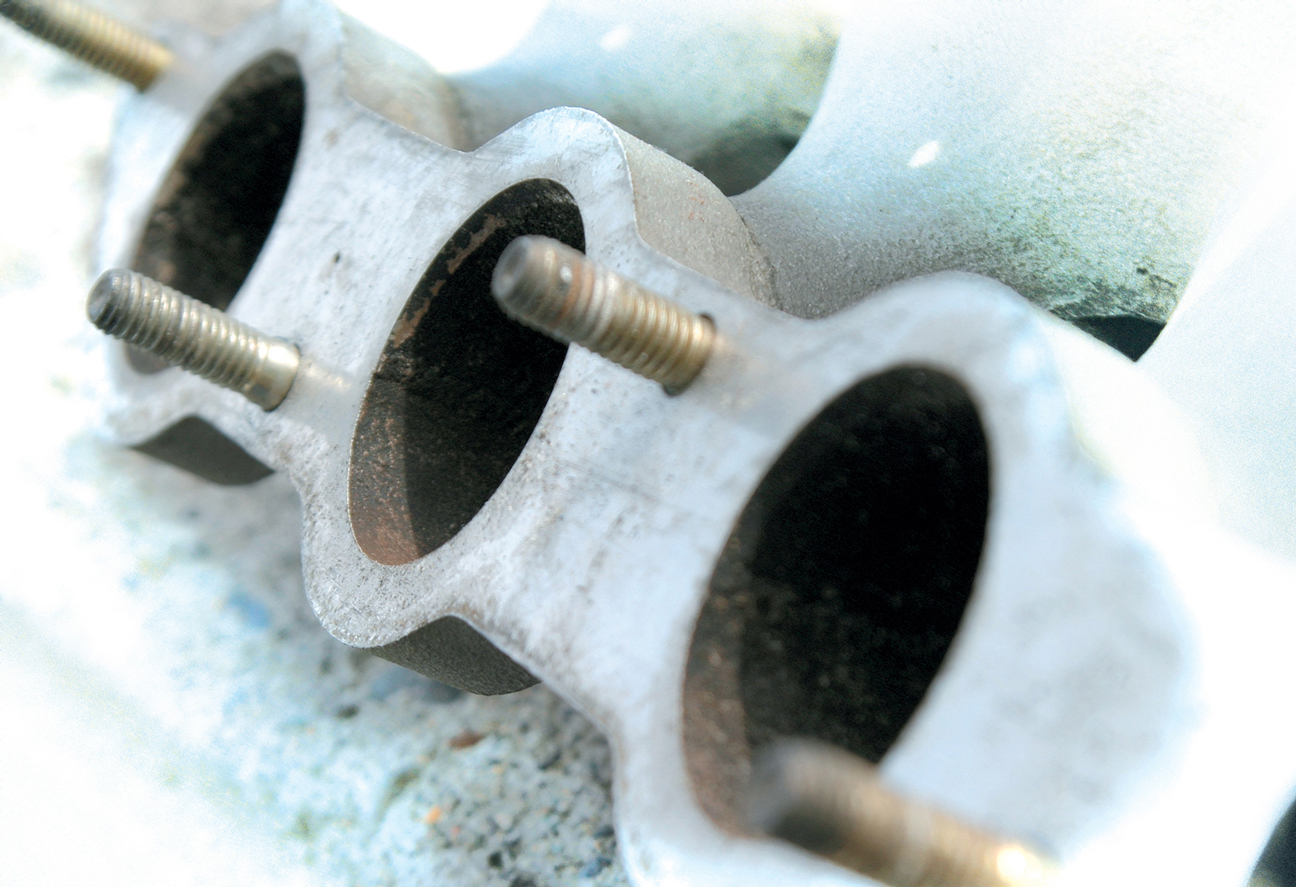

Most every pre-’48 car came with fender/body welting, consisting of a simple combination of a narrow strip of vinyl (or similar material) folded over a small-diameter woven cord and glued shut. Its purpose was, and still is, to insulate one piece of body metal from another when bolted together—not an electrical or temperature insulation, but essentially to eliminate squeaks and rattles, and to prevent paint from chipping (or cracking) as the two pieces flexed and vibrated together under normal road use. Generally referred to as fender welting, this product can also be found throughout certain car models; used to mount grilles, running boards and bumper gravel shields.